Disclaimer - This is a news site. All the information listed here is to be found on the web elsewhere. We do not host, upload or link to any video, films, media file, live streams etc.

Kodiapps is not responsible for the accuracy, compliance, copyright, legality, decency, or any other aspect of the content streamed to/from your device.

We are not connected to or in any other way affiliated with Kodi, Team Kodi, or the XBMC Foundation.

We provide no support for third party add-ons installed on your devices, as they do not belong to us.

It is your responsibility to ensure that you comply with all your regional legalities and personal access rights regarding any streams to be found on the web. If in doubt, do not use.

Disclaimer - This is a news site. All the information listed here is to be found on the web elsewhere. We do not host, upload or link to any video, films, media file, live streams etc.

Kodiapps is not responsible for the accuracy, compliance, copyright, legality, decency, or any other aspect of the content streamed to/from your device.

We are not connected to or in any other way affiliated with Kodi, Team Kodi, or the XBMC Foundation.

We provide no support for third party add-ons installed on your devices, as they do not belong to us.

It is your responsibility to ensure that you comply with all your regional legalities and personal access rights regarding any streams to be found on the web. If in doubt, do not use.

Kodiapps app v7.0 - Available for Android.

You can now add latest scene releases to your collection with Add to Trakt. More features and updates coming to this app real soon.

Kodiapps app v7.0 - Available for Android.

You can now add latest scene releases to your collection with Add to Trakt. More features and updates coming to this app real soon.

Lumina 2024 - Movies (Mar 9th)

My Husband the Cyborg 2025 - Movies (Mar 9th)

Flow 2024 - Movies (Mar 8th)

In the Summers 2024 - Movies (Mar 8th)

Old Guy 2024 - Movies (Mar 8th)

Captain America Brave New World 2025 - Movies (Mar 8th)

Moana 2 2024 - Movies (Mar 7th)

Ghost Cat Anzu 2024 - Movies (Mar 7th)

The Silent Planet 2024 - Movies (Mar 7th)

Tuesday 2024 - Movies (Mar 7th)

Plankton The Movie 2025 - Movies (Mar 7th)

CHAOS The Manson Murders 2025 - Movies (Mar 7th)

George A. Romeros Resident Evil 2025 - Movies (Mar 7th)

The Little Mermaid 2024 - Movies (Mar 7th)

Bloat 2025 - Movies (Mar 7th)

Confessions of a Romance Narrator 2025 - Movies (Mar 6th)

Woods of Ash 2025 - Movies (Mar 6th)

Agents 2024 - Movies (Mar 6th)

Barbie and Teresa Recipe for Friendship 2025 - Movies (Mar 6th)

Picture This 2025 - Movies (Mar 6th)

Mozarts Sister 2024 - Movies (Mar 5th)

Tournament of Champions - (Mar 10th)

The White Lotus - (Mar 10th)

Cóyotl, Hero and Beast - (Mar 9th)

Countryfile - (Mar 9th)

Snapped- Killer Couples - (Mar 9th)

Deadline- White House - (Mar 9th)

The Sunday Show with Jonathan Capehart - (Mar 9th)

Prosecuting Evil with Kelly Siegler - (Mar 9th)

The Last Drive-in with Joe Bob Briggs - (Mar 9th)

Crufts - (Mar 9th)

The Great Pottery Throw Down - (Mar 9th)

The Potato Lab - (Mar 9th)

Love Your Weekend with Alan Titchmarsh - (Mar 9th)

Dancing on Ice - (Mar 9th)

Forensics- The Real CSI - (Mar 9th)

Australian Idol - (Mar 9th)

Family or Fiance - (Mar 9th)

48 Hours - (Mar 9th)

Sunday Brunch - (Mar 9th)

The Tommy Tiernan Show - (Mar 9th)

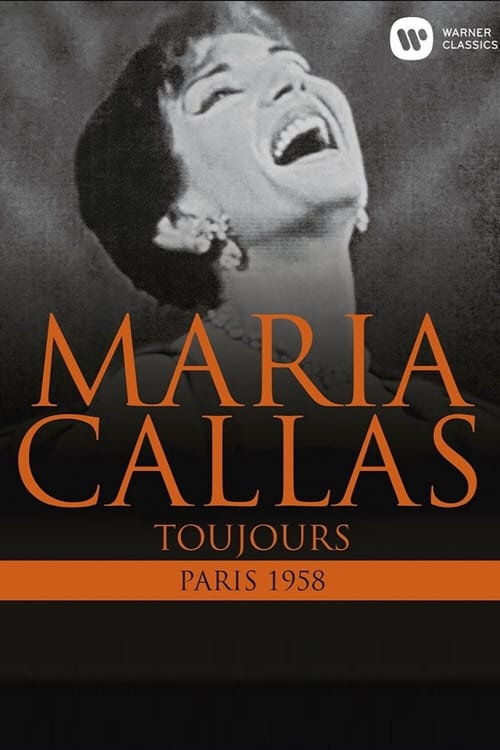

**Maria Callas - Paris 1958** Callas’s Paris debut came relatively late in her career. She sang her first opera in 1939, had her first Italian successes at Verona in 1947, made her South American debut in 1949 and reached La Scala in 1950, London acclaimed her in 1952, Chicago in 1954, Berlin in 1955, Vienna ’56. That same year also saw her long-expected, long-delayed arrival at the Metropolitan, New York, and the next brought her back home to Athens. Venice, Rome, Palermo, Mexico City, Philadelphia, Dallas, Madrid, Lisbon and Edinburgh were other cities to witness the triumphs and controversies of this extraordinary decade. And then at last came Paris: the city she was to make her home and in which she was to die. In defence (if it was felt to be needed) loyal Parisians might have argued that the point was not that Paris was late, but rather that this first appearance at the Opéra was the final summit, the ultimate conquest, and that the splendour of the occasion in the Palais Garnier on that December night bore witness to the fact. Had any other city given her quite such a magnificent welcome? Where else had the head of state turned out in the pouring rain, with all that was elegant, famous and rich packing the house for a show that played to a whole continent beyond its walls? And then, when she appeared on stage, that slender, stylish figure, in the gown variously described as scarlet and champagne, adorned by a million dollars’ worth of loaned jewellery, descended the staircase and stood before this brilliant audience, was it not exactly the scene of which dreams are made? At the centre of the stage she stood, which at that moment felt like the cultural centre of Europe if not of the world. At the very least it provided a gratifying end to a year which had begun in anger and continued in turbulence. 1958 is still remembered as the year of the Rome walk-out. For Callas, the new year had opened with throat-sprays and panic: the voice had disappeared and Norma loomed. This was to be the opera of the new season’s first night, which would be attended by the President of Italy and his wife; what is more, the performance was to be broadcast and for the part of Norma no understudy or substitute was available. So Callas sang the first act. At the end came hisses and boos, exacerbated by the high price of seats and the high esteem in which she was known to be held by the scorned Milanese, and she left the theatre. It was also believed that the success of the Adalgisa and Pollione in that act (Miriam Pirazzini and Franco Corelli) had something to do with it. Whatever the reason, no more of Norma was given that night, and after an unusually long interval everybody went home, the President leading the way. Scandal erupted in the morning, and there were demonstrations and even fights. Parliament discussed the matter and newspaper editors wrote leading articles on it. Callas had her defenders, but from that time onwards the legend of the tigress followed her wherever she went. The spring brought American successes, though they were prefaced by a court hearing and a reprimand from the American Guild of Musical Artists concerning breach of contract in San Francisco. Then there were troubles with mother and Rudolf Bing, triumphs and insults in Milan, a bitter-sweet farewell to La Scala, and a fraught, flawed, but unforgettable Traviata in London. A concert-tour in the States, a brilliant but exhausting Medea in Dallas, an equally wearing and highly publicised contretemps with the Metropolitan, and she was ready to come to Paris. Another factor was involved too, a more constant and worrying one than any of these individual events. After all, everything finally depended upon the voice. It had gone through hard times: the Isoldes, Briinnhildes and Turandots of earlier years could not fail to have left their mark, and then the exploitation of the top notes in the dazzling and briefly triumphant creation of the dramatic coloratura, all had to be paid for. Even in the prime years culminating, perhaps, in the achievements of 1955, the voice and its production had raised misgivings, quietened only by the genius that so clearly inspired her performances. But Paris had missed her in those years, and the voice which uttered Norma’s rebuke to the warmongering druids was not the sweetest in the world, nor yet the mightiest or firmest. In the ‘Casta diva’ too, there must have been some in the audience who allowed an honest doubt to cross their minds. After the publicity, the scramble for tickets, the dressing-up, the fanfares and guard of honour, was this the voice that launched all that ballyhoo? Experienced listeners to Callas would not be unduly upset by this kind of experience: it is not unfamiliar, and, as they would know, faith is usually rewarded. At some point, and without having to wait inordinately long for it, would come one of those moments when they would know that this is Callas, uniquely potent in her way with a phrase, a character or an inflection. In the Paris performance the thrill of recognition comes, if not with the first phrase, then with the second - “voci di guerra”, with its tone of command and hint of power in the lower register. In the aria there are those descending chromatic scales, magical as ever; and for the viewer it is fascinating to see how, when chaos threatens with the chorus’s entry in disarray, the smile momentarily freezes on her lips till she signals her own entry with a strong conductor’s downbeat and carries on smiling. The second recitative, with its pleasing reference to the blood of the Romans, brings her close; but it was really for the Trovatore aria and ‘Miserere’ that Parisians had to wait in order to know for certainty that it was indeed the fabled “impératrice du bel canto” that they had in their midst. For this the lights are lowered. It would be absurd to say that Callas needed a stage, for after all, her recordings were made in a studio and were never studio-bound; but still, a spotlight to her was as sunlight to a flower, and whereas the stage was her natural element she was mysteriously taken out of it when that same stage became a concert platform. Here, in the ‘Miserere’ scene, she is able to enter the night of Leonora’s torment and so to find her way into that desperate, resolute soul who spins such luminous phrases out of her darkened yearnings. The technical perils are evident as she sings, yet so often are surmounted with genuine mastery. Then in the ‘Miserere’ itself, the cry after Manrico’s first solo, “Sento mancarmi”, has thrilling strength and dramatic concentration in it, as has the whole of her singing in the second verse. After that, the smiles and wiles of ‘Una voce poco fa’ might be less than welcome, but here too the mastery conquers. More than an exhibition of brilliant technique, it shows something of the gift that Callas had for comedy, unexpected and sometimes disputed maybe, but as convincing here in its gaiety as the Trovatore had been in its sense of tragedy. These, I think, are the memories to go into store from the first half of that evening’s programme. After the interval, the second act of Tosca has Callas on stage and in costume. This, with Tito Gobbi playing his unforgettable Scarpia, might have been expected to come as the climax, and perhaps for many it was; yet, bereft of the two outer acts, with their tenderness and quieter lyricism, this brutal scene lays itself open to some over-familiar charges which it can withstand much better in context. Besides, there is always the difficulty of ‘live’ opera filmed: the scale and nature of the acting are gauged for the theatre rather than for the cameras. Even so, it is something to see these two supreme actor-singers of their age appearing together on stage, as they were here, for the first time in this opera. Beside them, Albert Lance, an Australian whose considerable career was Paris-based, has very much the stage-manner of the traditional opera singer. He produces some good, sturdy tone for all that, and his second “Vittoria!” is such a stunner that he relapses for the rest of the part into what for him was the more familiar French (though in fairness it should be added that he was standing in for the much older José Luccioni whose name was printed in the programme and who was said to be “souffrant”). For Gobbi, the vibrancy of his voice impresses at least as much as does the suave malevolence of his characterisation. For Callas, it is good to hear the voice freed, and interesting to see her take the first half of ‘Vissi d'arte’ from the back of the stage. Phrases haunt: the very feminine “non posso pit”, the tearful “Vedi...ecco, vedi”, the sudden thrill of determination in “Si, per sempre”. The face haunts too - those eyes, wide first with scorn, then with horror as the appalling situation becomes clear. Yes: the Parisians (and Chaplin, Onassis, Brigitte Bardot and the Windsors among them) would have had plenty to mull over. 450 of them were given a splendid supper afterwards: I wonder how much of the conversation there turned upon the cantilena of Norma’s invocation, the mischievous Rosina, the tormented Tosca, the arched phrases of Leonora as she sighs forth her soul outside her lover's prison where monks chant the ‘Miserere’... © **J.B. Steane**, 1991. Booklet for the 1080i Blu-ray edition from _Warner Classics_ (825646054122), released on 06 November 2015.

Audiences went wild for Bartlett Sher’s dynamic production, which found fresh and surprising ways to bring Rossini’s effervescent comedy closer to them than ever before. The stellar cast leapt to the challenge with irresistible energy and bravura vocalism. Juan Diego Flórez is Count Almaviva, who fires off showstopping coloratura as he woos Joyce DiDonato’s spirited Rosina—with assistance from Peter Mattei as the one and only Figaro, Seville’s beloved barber and man-about-town.

It is a rare opera indeed that calls for one soprano diva and no fewer than six tenors. Mary Zimmerman’s fanciful production of Rossini’s drama, designed by Richard Hudson and with choreography by Graciela Daniele, provides the perfect setting for superstar Renée Fleming’s captivating performance of the title role. A beautiful but evil sorceress in the times of the Crusades, Armida sets out to regain the love of the Frankish knight Rinaldo (Lawrence Brownlee) by putting her magical spells on him. She at first succeeds to draw him into her web of sorcery, but ultimately divine intervention—and his fellow soldiers—free Rinaldo from his enchantment—much to the vengeful fury of Armida and her demons.

Short subject on how fashion is created- not by the great couturiers, but on the street.

A celebration of love and creative inspiration takes place in the infamous, gaudy and glamorous Parisian nightclub, at the cusp of the 20th century. A young poet, who is plunged into the heady world of Moulin Rouge, begins a passionate affair with the club's most notorious and beautiful star.

Richard Eyre’s stunning new production of Bizet’s opera was the talk of the town when it was unveiled on New Year’s Eve 2009. Elīna Garanča leads the cast as the iconic gypsy of the title—a woman desired by every man but determined to remain true to herself. Roberto Alagna is Don José, the soldier who falls under her spell and sacrifices everything for her love, only to be cast aside when the toreador Escamillo (Teddy Tahu Rhodes) piques Carmen’s interest. With dances created by star choreographer Christopher Wheeldon and conducted by rising maestro Yannick Nézet-Séguin, this Carmen brings every aspect of Bizet’s tale to thrilling life, from its lighthearted beginning to its inevitably tragic climax.

Robert Lepage’s remarkable Met Opera production of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen, the 2013 Grammy Award Winner for Best Opera Recording, is now available as individual DVDs. Siegfried features Bryn Terfel, Jay Hunter Morris, and Deborah Voigt, with Fabio Luisi conducting.

Ring Cycle, pt 4. Siegfried is drugged and tricked into kidnapping his wife, since she has the Ring now. More double-crossings, Siegfried ends up dead. Brunnhilde has had enough of this, tosses the Ring into the river and torches the place.

Adaptation of John Gay's 18th century opera, featuring Laurence Olivier as MacHeath and Hugh Griffith as the Beggar.

Bizet’s rarely heard opera returned to the Met for the first time in a century on New Year’s Eve 2015, in Penny Woolcock’s acclaimed new production. Star soprano Diana Damrau sings Leïla, the virgin priestess at the center of the story. Matthew Polenzani and Mariusz Kwiecien are Nadir and Zurga, rivals for Leïla’s love who have sworn to renounce her to protect their friendship—and who get to sing one of opera’s most celebrated duets, “Au fond du temple saint.” Nicolas Testé is the high priest Nourabad and Gianandrea Noseda conducts Bizet’s supremely romantic score.

A ruthless real estate agent discovers a passion for piano and auditions with help from a young virtuoso, but the pressures of his corrupt career threaten to derail his musical aspirations.

Disciplined Italian composer Antonio Salieri becomes consumed by jealousy and resentment towards the hedonistic and remarkably talented young Viennese composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.