Disclaimer - This is a news site. All the information listed here is to be found on the web elsewhere. We do not host, upload or link to any video, films, media file, live streams etc.

Kodiapps is not responsible for the accuracy, compliance, copyright, legality, decency, or any other aspect of the content streamed to/from your device.

We are not connected to or in any other way affiliated with Kodi, Team Kodi, or the XBMC Foundation.

We provide no support for third party add-ons installed on your devices, as they do not belong to us.

It is your responsibility to ensure that you comply with all your regional legalities and personal access rights regarding any streams to be found on the web. If in doubt, do not use.

Disclaimer - This is a news site. All the information listed here is to be found on the web elsewhere. We do not host, upload or link to any video, films, media file, live streams etc.

Kodiapps is not responsible for the accuracy, compliance, copyright, legality, decency, or any other aspect of the content streamed to/from your device.

We are not connected to or in any other way affiliated with Kodi, Team Kodi, or the XBMC Foundation.

We provide no support for third party add-ons installed on your devices, as they do not belong to us.

It is your responsibility to ensure that you comply with all your regional legalities and personal access rights regarding any streams to be found on the web. If in doubt, do not use.

Kodiapps app v7.0 - Available for Android.

You can now add latest scene releases to your collection with Add to Trakt. More features and updates coming to this app real soon.

Kodiapps app v7.0 - Available for Android.

You can now add latest scene releases to your collection with Add to Trakt. More features and updates coming to this app real soon.

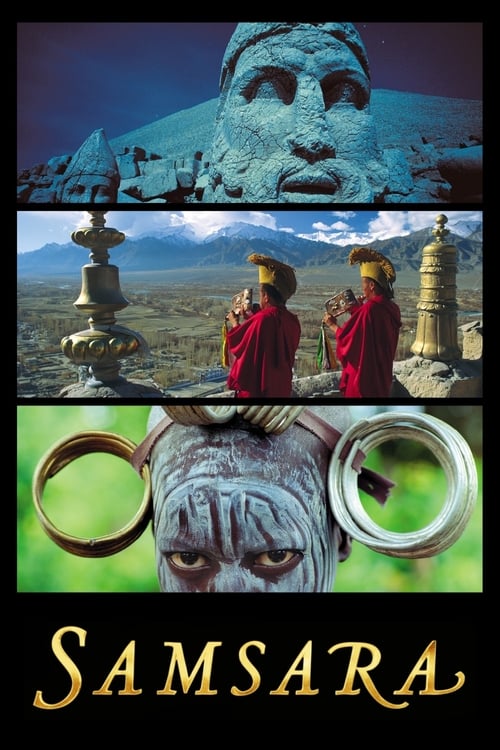

In 1993, filmmakers Ron Fricke and Mark Magidson presented a deeply moving portrait of features universal to all human societies, warned of ecological collapse, and depicted how technology was changing our lives in Baraka. Shot on 70mm film in 30-odd countries, this was one of the most visually impressive films ever made, and its lack of any dialogue or narration allowed viewers to engage in their own individual reflections about the panorama on the screen. Two decades later, the team returned with Samsara, a sequel that wasn't really necessary. One reason that Samsara is not very good is that it often seems a shot-for-shot repeat of Baraka. The filmmakers revisit many of the same locations (such as Thai prostitutes, a chicken-processing plant, home appliance factories, landfill gleaners). Again Buddhism, the Ka'aba and high church Christianity are depicted, but because the film does not go on to any other religions than what was on Baraka, these rituals feel this time like cheap exoticism instead of unquenchable anthropological curiosity. SAMSARA also lacks the dramatic arc of Baraka, coming across as a random succession of images instead of the journey from sacredness to horror and back that we found in its predecessor. That is not to say that Samsara is completely without interest. There is an astonishing clip of performance artist Olivier de Sagaza, and the freakish Dubai landscape is depicting in a detail that few (even those who have been there) have seen. Samsara is all in all a darker film, and while depictions of the wreckage of Katrina, a Wyoming family that are proud to own an arsenal of guns, and a wounded veteran may fail to really shock viewers in the West who have already been exposed to such images for years, scenes of garish funerals in Nigeria and Indonesian men making the rounds in a sulphur mine (even though they know it is killing them) are stirring and memorable. Of course the visuals are rich, and in Bluray format on my HD projector the film is just as stunningly detailed as its predecessor. However, Samsara lacks enough new things to say, it surprisingly doesn't offer continual rewards on rewatching, and just by the fact that it exists out there it potentially dilutes the impact of Baraka, once a singular film. I was entertained enough to give this a 3-star rating, but I would still recommend Baraka, and even for those who have seen and loved Baraka, I would not recommend moving on to this film.

A day in the city of Berlin, which experienced an industrial boom in the 1920s, and still provides an insight into the living and working conditions at that time. Germany had just recovered a little from the worst consequences of the First World War, the great economic crisis was still a few years away and Hitler was not yet an issue at the time.

A woman narrates the thoughts of a world traveler, meditations on time and memory expressed in words and images from places as far-flung as Japan, Guinea-Bissau, Iceland, and San Francisco.

Commissioned to make a propaganda film about the 1936 Olympic Games in Germany, director Leni Riefenstahl created a celebration of the human form. This first half of her two-part film opens with a renowned introduction that compares modern Olympians to classical Greek heroes, then goes on to provide thrilling in-the-moment coverage of some of the games' most celebrated moments, including African-American athlete Jesse Owens winning a then-unprecedented four gold medals.

Commissioned to make a propaganda film about the 1936 Olympic Games in Germany, director Leni Riefenstahl created a celebration of the human form. Where the two-part epic's first half, Festival of the Nations, focused on the international aspects of the 1936 Olympic Games held in Berlin, part two, The Festival of Beauty, concentrates on individual athletes such as equestrians, gymnasts, and swimmers, climaxing with American Glenn Morris' performance in the decathalon and the games' majestic closing ceremonies.

The personal stories lived by the Uncle, the Father and the Son, respectively, form a tragic experience that is drawn along a line in time. This line is comparable to a crease in the pages of the family album, but also to a crack in the walls of the paternal house. It resembles the open wound created when drilling into a mountain, but also a scar in the collective imaginary of a society, where the idea of salvation finds its tragic destiny in the political struggle. What is at the end of that line? Will old war songs be enough to circumvent that destiny?

A paralysingly beautiful documentary with a global vision—an odyssey through landscape and time—that attempts to capture the essence of life.

A real-time reconstruction of time-lapse photographs taken on board the International Space Station by NASA’s Earth Science & Remote Sensing Unit. The film is scored with musical selections from three albums by Phaeleh (producer Matt Preston): Lost Time, Illusion of the Tale, and Somnus. The music directly influenced the choice of material used in the film. The film's duration is approximately the length of time it takes ISS to orbit the Earth once: 92 minutes and 39 seconds. Meditate on the beauty of our planet.

May Pang lovingly recounts her life in rock & roll and the whirlwind 18 months spent as friend, lover, and confidante to one of the towering figures of popular culture, John Lennon, in this funny, touching, and vibrant portrait of first love.

An exploration of technologically developing nations and the effect the transition to Western-style modernization has had on them.